Just 25 minutes south of Oklahoma City, on the border of peaceful Route 62, you’ll find Newcastle High School, which protrudes from the flat soil and buttresses itself abruptly, like an invasion of modernism. A man with luminous eyes is inside the gym, and he’s a firestorm. By any measure, he is not slim. Actually fashioned from marble. Strong and quick, he is. He captivates and frightens with his fabricated rage.

He clenches his jaw. A furrow forms on his forehead. His profanity is careless verse. You find yourself wondering if he’s indeed enjoying himself. In more ways than one, the annual Blue and White scrimmage that kicks off the Thunder’s training camp serves as a means of connecting with fans.

Every call is argued by Russell Westbrook Jr.

On October 4, 2015, at Newcastle High School in Newcastle, Oklahoma, Russell Westbrook (#0) and Nick Collison (#4) of the Oklahoma City Thunder showed their support during the annual Blue vs. White scrimmage during training camp. Important Notice for You

Getty Images/Layne Murdoch Jr.

Serge Ibaka, a power forward for the Thunder, is becoming more and more irritating to him. The Thunder’s pick-and-roll defense is completely out of practice since this is their first official game together since the end of the regular season.

According to Westbrook, “Man, we need to go small or something” in response to Serge’s foolish actions. How challenging is it?”

To soothe Westbrook, Durant places his big right hand on the nape of his neck. He frequently engages in this act.

Coach Darko Rajakovic’s assistant, who is on the white team, tries to reassure Westbrook.

Please tell me what you need from me.Rajakovic affirms. “Just tell me, tell me.”

There is no response from Westbrook.

Steps forward, Maurice Cheeks.

“What’s wrong?”With an air of casual ease, the Thunder assistant coach poses the question.

“No one’s pitching in!Westbrook begs. “If I cross over, someone needs to come and get me!” I’m going under because of that.

“However, you forfeited three going under,” Cheeks points out.

After giving it some thought, Westbrook finally says, “F–k it.”

He has himself re-enrolled.

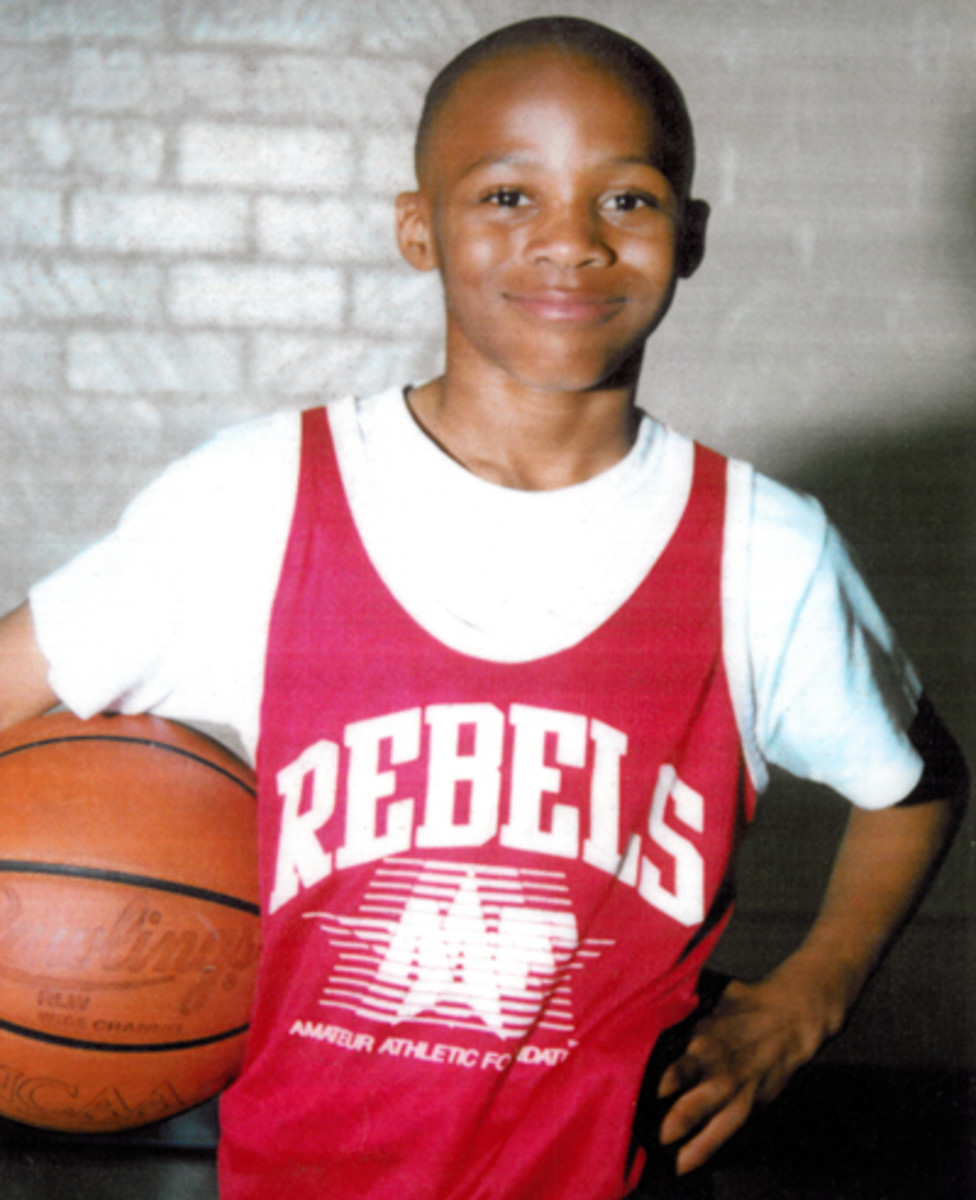

Russell Westbrook when he first entered the NBA.

Beginning his NBA career, Russell Westbrook.Getty Images

There is no way to damage Compton Avenue. Surely it is.

This frayed asphalt ribbon is beautiful. A cadence. A chronicle. It places unjust demands on people. The object is aware of discomfort.

Yet not every kind of suffering is bad. Sometimes it’s attached to a strange hope that only locals can understand.

Ultimately, this is a site of birth.

This is Russell Westbrook’s hometown.

The boy with the sculpted jaw and high cheekbones knows this concrete; he deals in an odd mix of tailored clothing and contrived anger. He is familiar with all of this agony, all of this history.

You might be able to find his line of sunglasses at Barney’s. His Vine-inducing dunks are getting more and more bold. His enthusiasm is confounding. No one could have predicted his rise to recognition and notoriety on the court. Yes, not even him. Simply told, it’s all nonsensical.

Let’s start with Compton Avenue. There’s also Jesse Owens Park. Another option would be the living room of his parents’ small apartment.

“I never thought I would be in the NBA,” says Westbrook. Many players in the NBA now have talent that dates back to when they were eight years old. I was horrible till I was seventeen.

Every superhero has a different backstory as their hero. Being reluctant to take on heroic roles is common, but it should be handled with ambition and tenacity.

Everybody has a place here. Your past is the one aspect of you that you cannot change. It’s an indispensible strand of DNA as solid as Compton Avenue. Its half-life has an infinite duration.

Buildings that are on fire, streets that are always lit up with flashing red and blue lights, and steel-caged booze stores do not lessen or characterize those who survived such a desolation.

It’s just home at other times.

He acknowledges that it was not an easy transition for him to become the man he is today. I discovered that growing up, Los Angeles was my home. Being from my hometown makes me very proud.

After veering down Compton Avenue, one can find the excursion’s starting location by turning left on 41st Street.

Russell Westbrook in his senior year at Leuzinger High School in Lawndale, California.

Russell Westbrook, a senior at Leuzinger High School in Lawndale, California (Getty Images)

Son Also Rises

Around 6:30 in the morning, Ben Howland went into the Leuzinger High School gym in Lawndale, California. The UCLA head coach was pleased, despite never having seen Westbrook in person. The players were still nowhere to be found, and Howland was the only one in the gym other than a tiny child mopping the floor.

Westbrook’s recruitment wasn’t given high priority. Not one of Howland’s precious McDonald’s All-Americans, at all. He knew how fast he was. About his passionate defense. He believed that having him as a backup would help his freshman sensation, Darren Collison. The student section of Pauley Pavilion would certainly grow to love him.

Reggie Morris, the Leuzinger’s head coach, met him a short while after. Morris assured him throughout their brief exchange that he would be impressed with what he saw in Westbrook.

Has Russell vanished?””What desires do you have?Howland asked.

“Right there,” Morris answered. Someone is pushing the broom.

After ending the game, Westbrook gathered his teammates in the locker room. Then he gathered them all into a tight ball and began to yell at them as though the gym was crowded on game night. Westbrook sprinted onto the court with his teammates right after him, setting up a layup line and other exercises right away.

Howland remembers that he was initially introduced to Russell Westbrook in a leadership role. “It was really amazing.”

Howland addressed UCLA assistant coach Kerry Keating, who had played a key role in securing Westbrook’s recruiting, when he returned to campus.

Howland said, “This kid isn’t built to play point guard.”

“I never said he was a point guard,” countered Keating. Ah, I see. “I just mentioned that he could play.”

The truth was that they had no idea what they owned. They knew they had affections for him despite this. It was unclear to his colleagues why Keating had been surreptitiously observing him for a few years.

Donny Daniels, an assistant at UCLA, didn’t realize why until he saw Westbrook play against Westchester in a high school tournament. After missing two airballs, deciding poorly, and growing agitated, he forced the shot. When they are about to lose their chances to receive scholarships, kids play in that way.

Daniels’s only thought was, “This kid can play.”

His drive, enthusiasm, and rivalry affected nearly every play in the game. He had the advantage in defense because of his length and speed. He made most of his mistakes when he tried to incorporate other people. He took everyone by surprise with the lift, rotation, and release of his jump shot. He tumbled, diving to the floor.

Daniels yells, “You don’t judge a kid,” following a subpar performance. He was so full of potential. It would only take tossing the ball into the hoop. Man, it was raw.

Keating saw Westbrook play six times in his senior year, which was the most the NCAA permitted at the time. During games, he could easily make sure his dad saw him because there were no other scouts around. He would tolerate awful games with lengthy wait times.

His choice to sign a 5’9″ guard who couldn’t shoot was questioned by many.

Keating recalls that “he was this rugrat who played like a bat out of hell.” He resembled a crazy dog.

The ferocious, professional pickup baller Westbrook’s father played a major role in shaping his son’s chaotic style by taking him to different gyms and parks in the community to shoot jump shots and drills he had devised.

According to Jordan Hamilton, a fellow Compton native and previous first-round draft pick, “it was all work-ethic stuff.” “They would engage in combat training.”

The youngster was made to do push-ups, sit-ups, continuous sprints, sandbox agility drills, and other such activities to instill in him the value of exerting himself.

He was always told to “outwork them” by his father.

Furthermore, Westbrook wasn’t just small; he was minuscule. He could have disappeared with a fast spin to the side, and most people would not have noticed.

To lift the boulder-sized chip and place it firmly on Russell’s narrow shoulders, they had to cooperate. Russell had started to mold his mind in the same manner that he had fashioned his game, having learnt from his father to detest the way it felt and to never give up. It was simple to ignore, mistrust, and disregard him.

Westbrook’s character is rooted in the idea that individuals should be accountable for their acts, as he states, “I never really worried about what people thought about me.”

His family was impoverished; they constantly lived in dilapidated apartments in dubious neighborhoods, and Shannon, his mother, would raid thrift shops in search of inexpensive clothes for her sons.

My mother used to dress me when I was a child. She would pick out my clothes and made sure I looked my best all the time. We weren’t wealthy, but Mom still made sure I got all I needed.

After Westbrook’s football misdeeds, Russ Sr., a Compton native who had his fair share of legal run-ins, decided to take extra measures because he valued a basketball scholarship more than anything else.

When Westbrook was a teenager, his parents forced him to spend a lot of time inside in an attempt to keep him off the streets.

Westbrook recalls, “My dad didn’t want me to go to Washington because it was a pretty bad school.” “I moved to Leuzinger, but things didn’t really improve there.”

Morris was there, though, because he was one of the few people Westbrook Sr. allowed to influence his son’s development.

Arriving as a 5’8′′ freshman with size-13 feet, he didn’t make the transition to the varsity squad until his junior year. Not a single elite AAU team or well-known summer camp issued invitations. Westbrook avoided reading newspaper stories about the accomplishments of other players and rarely watched local basketball.

He acknowledges that he didn’t look up to the best players in the city. To be honest, I never really thought about it. Staying out of trouble at home was more important to me than watching games or following athletes.

His third-team All-State award came after a monster season of 25.1 points, 8.7 rebounds, and 3.1 steals per game; this was the product of ten years of drills combined with an unplanned growth spurt—he shot up five inches before his senior year.

Keating’s persistent efforts to gain the trust of the Westbrook family paid off, as a sleeper signee with considerable upside was on the way.

Nevertheless, there was a bug.

Jordan Farmar held the key to Westbrook’s future with the Boston Bruins. There was no way out of it at all. Farmar’s only chance of getting a scholarship was to turn pro. Until Keating accomplished this, all of his efforts would have been in vain.

Howland had thought Farmar would stay put.

“I don’t think we’ll need Westbrook,” the coach would say.

But as far as Keating knew, Farmar was determined to succeed big time. In real life, he would figure Darren Collison out to demonstrate his aggression and authority.

The assistant drove Howland and Keating’s first car, a brand-new 5 Series BMW, fast down the congested 405 in pursuit of the Hawthorne exit. Not too far along Crenshaw was where Russell and his brother Raymond hung a right, leading to the tidy two-bedroom apartment they called home.

The living room walls displayed trophies and other family photographs.

When the coaches came, Russell was sitting between his parents on the couch in his shorts and flip-flops. He was tall and had his legs wide apart. In his lap, his palms were facing downward. He rarely said anything.

As Howland was enumerating the several courses the school provided, Keating had another thought.

He says, “I was amazed at how big his hands and feet were.” “This child is going to grow up even more!”

Westbrook was not unknown, even in spite of his lack of star power. Following his significant interest being shown by Arizona State, he made an official campus tour. The day after his return, Farmar joined in the military.

Westbrook signed his letter of intent with UCLA without delay.

Westbrook and his partner Kevin Durant are at the Team USA training camp.

Westbrook’s accomplice, Kevin Durant, at the Team USA training camp. Getty

Teams of three people were assigned to the participants. LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony, and Kevin Durant were positioned on the left side of the court. Stephen Curry, Westbrook, and Chris Paul were on the other side.

The whole basketball world descended onto the UNLV practice gym in August for Team USA’s mandatory three-day minicamp.

Two of John Calipari’s most recent first-round draft picks, Anthony Davis and John Wall, were seated on the sidelines as the coach grinned widely.

Blake Griffin was shooting mid-range jumpers from a pull-up stance on the other side of the court. His collegiate coach, Jeff Capel, was assisting him in grabbing rebounds.

Head coach Mike Krzyzewski visited each station, stopping to chat and offer encouragement to various basketball influencers.

The three-man mega-teams seemed to be engaged in a fierce shooting session. During the catch-and-shoot play from the short corner three, Curry made every shot he took.

Melo and KD thrive in triple-threat situations, so it was a no-brainer for Melo to shoot out of that position. They had an easy time winning.

After then, the mid-post players started to make turnarounds after getting an entry pass. Durant swished at a fadeaway. Then CP3 launched a rainbow from his side. The volume of their exchanges increased as they carried on hurling insults across the highway at one another. LeBron would always create a sound effect when Melo would hit his lowest point.

At last, Westbrook had stood up. He picked up an entry pass. He turned his back on the basket and braced himself. The new assistant to Thunder, Monty Williams, was tasked with applying token pressure. With a gasp from the USA Basketball assistant coach, Westbrook turned and smacked his shoulder into Williams.

Williams took a step back and looked at Westbrook.

Williams informed Westbrook that although it was a non-contact camp, they had experienced a similar situation the day before at another session. But when it came to his bragging rights, he let his inner Westbrook loose.

“I don’t give a damn,” Westbrook answered. Thus, “let’s go.”

Westwood’s Winter Storm

Growing up, Westbrook was quite private, but at UCLA, he made friends with everyone right away.

When he first laid eyes on the vast Westwood campus, he was seventeen years old and full of curiosity about the world outside South Los Angeles.

In the summer before his freshman year, he spent time getting to know basketball recruit Nina Earl, who grew up 40 miles away in Pomona. She seemed to balance him out, even though she shared his love for competition.

In a tone reminiscent of Russell Westbrook, she writes in her scouting report for UCLA, describing herself as “one of the fastest players on (the) team; excels in transition.”

“I would go up to Russell and tell him how much I admire that cute couple,” Howland says. Physical attraction was all that was needed for them to fall in love.

Westbrook rarely went back to his dorm room and instead made the most of his time on campus when he wasn’t playing or studying.

He frequently attended softball and track events and was rarely absent from a women’s basketball game. Going to Bruins football games with friends was customary.

Howland asserts that he would act in any situation. You know, he was the hottest on college.

He was drawn to people who were not like Westbrook in some way.

He felt a connection with Luc Richard Mbah a Moute. Undoubtedly, the amazing Luc was a senior citizen who owned a car and regularly traveled to the Saxon Suites apartments on De Neve Drive to pick up Russ after practice. The real connection, though, was that the small Cameroonian forward could introduce him to a different way of life. In addition to introducing Westbrook to hot Cameroonian cuisine, he introduced him to African hip-hop musicians, many of whose tracks the rookie downloaded.

He intended to ask Mbah a Moute, who shared a residence with Alfred Aboya (middle), about his upbringing in Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon. Aboya’s ambition to lead his own country as president was supported by Westbrook.

As a freshman, Westbrook shared a room on the road with Arron Afflalo, a fellow Angeleno and top scorer from the 2007 Bruins Final Four team.

Kevin Love and Russell Westbrook were UCLA teammates.

Russell Westbrook and Kevin Love as UCLA teammates. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

Afflalo recalls of him, “He was just a chill guy.” He was usually vibrant and immaculately groomed. He looked like any ordinary individual. All I remember doing was laughing a lot. Together, we had a terrific time. I wasn’t sure why we were paired up, but he was a great roommate.

In order to properly engage with the subject in his American Popular Culture class, Westbrook threw himself into his assignments and took advantage of his professor’s office hours.

“He was humble and friendly and unswaggery,” said his lecturer Dr. Mary Corey. “His intellectual curiosity was genuine.”

He never missed an opportunity to engage with the students, whether it was by striking up a conversation with aging scholars in their eighties or by snapping pictures with groups of visiting Chinese students.

In an effort to learn more about his players, Daniels would frequently pose spontaneous questions to them.

Which player is your favorite?He asked Westbrook the question after practice.

Westbrook responded by naming Pau Gasol. “Watching him play is just enjoyable.”

Daniels is still shocked by the response considering all the pompous celebs he might have chosen, but he gets it.

“Given his knowledge and appreciation of the game, it shouldn’t be surprising that Russell will always be different and choose the unexpected,” says Daniels.

Daniels claimed that the man “couldn’t be categorized as a hip-hop guy” either. He was intrigued by everything. But that curiosity had existed in him long before he enrolled at UCLA.

Growing up in Westwood was an absolute delight.

But Westbrook had a really difficult first two weeks of competition.

For him, it was all a mystery, as Keating remembers.

Howland says, “I was quite critical of him.” I could have pushed or become too hard on him at times.

Westbrook had to be the team’s safety valve during a defensive drill by coming back onto the court following a shot. Each time, it was the attacking boards he wrecked. Howland, getting angrier by the moment, threw him off the floor. Westbrook scowled as usual and mumbled something under his breath.

As time passed, Keating began to observe Westbrook closely, documenting his reactions to everything, including his facial expressions and vocal inflection.

And then it hit him.

Keating suggested Howland concentrate on the information rather than the speaker’s style of delivery.

It was a surprise, similar to discovering the first piece of a jigsaw puzzle. In addition to being more personable as a teacher, Westbrook began to develop as a collegiate athlete.

Howland trusted Arron Afflalo and Collison, a strong combination who thrived in his team-focused approach and could produce in the closing stages. Their attempts to slow Westbrook down were fruitless. Because the other players couldn’t keep up with his pace, the lineups that featured him felt out of place.

He moved at a speed that seemed unreal to Howland. “That was the only speed he could move.”

In nine minutes of action each game, Westbrook averaged a pathetic 3.4 points, 0.8 rebounds, and 0.7 assists.

Nevertheless, in the summer between his freshman and sophomore years, he would have a breakthrough basketball season. He would open his eyes at six in the morning. Every morning, I get up and head to the gym to work out with heavy weights and get my heart rate up.

At the former Me𝚗’s Gym on campus, Westbrook would play pickup basketball against any visiting local pros whenever summer school was in session. Westbrook tested his mettle against NBA greats like Carmelo Anthony, Kevin Garnett, and Kobe Bryant. There was not a single professional on the court that possessed the same speed and agility as him.

According to Mbah a Moute, no one offered to stand in for Russ.

Howland would run into former Bruins like Baron Davis and Earl Watson, who could not stand up to Westbrook’s persistent pursuit and enthusiasm, even though coaches were not allowed to watch summer sessions.

“They would just come up to me and say, ‘Wow,'” Howland remembers. “He lost it completely that summer.”

When he started every game as a sophomore, he displayed greater poise. During the whole forty-minute game versus Michigan State, he only made one mistake. That shot may come to him at any time. He took over for Darren Collison in the game. Because of his solid defense that kept opponents from drawing fouls, he was chosen as the Pac-10 Defensive Player of the Year.

After the season, Westbrook stopped by Howland’s office. He was thinking of signing up for the draft. Howland answered hesitantly. He believed Collison was leaving and had high expectations for Westbrook’s growth into a capable starting point guard during his junior season. Despite being ranked in the mid-20s by most draft boards, Howland thought that with more talent development, he could be a top-three pick.

Furthermore, he had begun to sense a connection with Westbrook as the center of the program.

Howland continues, “Most people dream of teaching a young man or woman like him.” How amazing of a leader he was. How positive he was. He greeted everyone he encountered. His positive attitude stunned everyone. His enthusiasm was infectious. He had incredibly high scores on all of the personality assessments. I was really attached to him.

Disorder and Disorder

The Seattle SuperSonics practice session finished twenty minutes ago. To begin the game, Earl Watson ascended the stairs to the head coach’s office. John P. Carlesimo intended to watch the game film of the Sonics’ upcoming opponent and answer any missed calls after the morning practice.

Watson knocked, and he opened the door for himself.

Watson suggested that he see the young one. “Him is the best player they have.”

The team needed a big man, even if they had their sights set on Westbrook. The Sonics weren’t impressed by him despite his stellar performance while playing for UCLA.

“However, Earl simply exuded energy,” says Carlesimo. He claimed that Westbrook was the best feature of the show. We started to give him our whole attention because he was so passionate about persuading.

After declaring his drought, Westbrook started working out frequently with coach Bob McClanaghan. Westbrook would travel three blocks each way to Santa Monica High School each day in order to work out vigorously in the hot gym for ninety minutes.

His favorites were the rough gyms. The worn-out rims, creaking floors, and fingerprinted backboards gave his exercises a gritty charm.

At some time, almost every coach and trainer who has worked with Westbrook has attempted to persuade him to slow down.

McClanaghan was a walk-on point guard for Syracuse from 1998 to 2001. McClanaghan remarks, “He’s such a freak athlete he didn’t know how to play slow.” The coach stated, “If he learned to play at different speeds, it would be more difficult to guard him.”

According to McClanaghan, the best players in the world, such as LeBron James, Dirk Nowitzki, and Kobe, all played slowly. In other words, they set up their defender by controlling the tempo and then using their talent to get the shots they wanted.

In this level, McClanaghan contends, slow is speedy. Instead of picking someone up, I’d want to slow them down.

From the beginning, Westbrook urged that McClanaghan work out daily, just like he would have on Thanksgiving with his father when he was twelve. “He desired to travel every day of the week,” McClanaghan declares.

To improve his clanky pull-up, McClanaghan said Westbrook would start at one hash mark, dribble rapidly to the opposite elbow, stop suicidally, and pull himself up straight. He was required to start at the foul line, run the entire length of the court, and then pull up at the opposing foul line—known as the “kll spot” due to the elbow—during another session.

Westbrook held a press conference to introduce himself.

Westbrook at his press conference for introduction, captured by Getty Images

The plan for the Sonics with their fourth-round pick was to practice with about twenty players. Center Brook Lopez of Stanford was ranked fourth out of their five options. Although he liked Westbrook’s athleticism, general manager Sam Presti wasn’t sure if he should start him next to Kevin Durant. Moreover, the club desperately needed a big player to bolster the defense.

During the draught, Carlesimo already had his pick in Lopez.

It’s just not common to find a 10-year major, says Carlesimo.

Presti saw the footage of Russell arriving 45 minutes early to the GM’s exercise in Santa Monica and knew he had his man.

Howland was there the night Russell Westbrook, the fourth overall choice, was chosen. He still has the SuperSonics cap that the valiant Leuzinger guard gave him that evening.

On July 2, while Carlesimo and his spouse were enjoying dinner to commemorate their tenth wedding anniversary, their phone rang just as their meals were being served. Presti informed the coach that the team’s relocation to Oklahoma City had been confirmed. They had to be in Oklahoma City since they had to find a new practice location and begin renovations the following day. Over the summer, Carlesimo had hoped to work with Westbrook, but the chance never presented itself. He was unable to bounce back from his previous setbacks throughout that season either.

After the Hornets defeated him by 25 points at home, Presti went into Carlesimo’s office and told him he was fired. He is no longer eligible for the 1–12 team. The players discovered out when assistant coach Scott Brooks boarded the plane and announced to the group that he was taking over.

It was now Brooks’ challenging task to mold Westbrook into the extraordinary talent that he was. A year later, his longtime assistant Rex Kalamian joined the squad and turned into his biggest ally.

According to Kalamian, there is no such thing as a week, month, or even year to build trust. That isn’t how it functions. He needs to recognize that you can assist him, whether it is with pointers on how to win a certain match or suggestions on how to raise his game. When he follows my advice and gets the desired results, the trust starts to develop. That’s when he starts to believe in you.

After playing with him for a while, Westbrook was so receptive to Kalamian’s coaching that the Thunder frequently gathered Kalamian over him in the closing minutes of games when their offensive package was limited to three or four plays.

Pulling an index card out of his suit jacket with the scheduled plays on it, Kalamian would give Westbrook alternatives based on matchups and scenarios.

That is the other side of trust, and Kalamian says, “He’d go down the list and say yea or nay.” We actually gave him permission to call the game.

Easy enough to ignore, easy enough to ignore no more. This is the same player that was once passed over by mid-level institutions despite being a four-time All-Star, an All-Star MVP, a scoring champion, and a gold medalist.

In the words of Kalamian, “What more can Russell Westbrook do to allay the doubts of his critics?””

Thank you, Scott Hirano.

The next basket decides who wins the Blue and White scrimmage. When Steve Novak becomes lost on a screen in a moment of confusion, Ibaka frees him. Novak receives a pass from youngster Cameron Payne and converts it into a three-pointer that beats the buzzer.

“Whoa, what an idiot you are!”Oh no!Westbrook exclaims. It’s untrue!”

He takes a lethal glance at Ibaka.

One unit screams incoherently, while the other leaps to the ground and encircles Novak.

Westbrook goes crazy and goes back to his bench. He takes the last bench seat and relaxes in. Sitting only a foot away, his chiseled physique emanates heat. There’s his deodorant on the air.

He’s staring straight forward. His rage has no boundaries. He must be alone himself right now. since it benefits not just him but also everyone else. He clenches his fists and keeps his hands in his lap.

Kevin Durant comes over and puts his right hand over his head in a quick gesture.

He says, “Way to go, Zero,” and walks away.

A handful of players approach him and touch his balled fists in his lap while offering encouraging remarks. They are taking precautions to make sure Westbrook doesn’t leave them high and dry. When he dons his vivid orange Jordan sneakers, children begin addressing him by his last name.

The new coach, Billy Donovan, approaches his best player warily.

Donovan says, “I thought you made a great pass on the second-to-last possession.” “Highly perceptive.”

Westbrook did not falter. He is staring straight ahead. In no situation. A little taken aback, Donovan remarks. With another stroke on the shoulder, he backs off softly and says, “Good stuff.” Westbrook looks forward and can not stop staring. He ignores everyone who comes near him.

This is how he conducts business. Donovan pauses, then looks away abruptly.

Westbrook says it doesn’t matter what other people think. “I don’t intend to.”

The one thing about who you are that you can never change is where you came from.

But Russell Westbrook is invincible.